Originally published on the Lumiere Festival Website May 8, 2019.

Her giant, billowing artworks respond to the wind and have re-shaped public spaces in five different continents. In 2015 we suspended Echelman’s touring sculpture, 1.26 Durham above the River Wear as part of Lumiere and in 2016, she created 1.8 London to float over Oxford Street for Lumiere London. Her artistic practice fuses the ancient craft of weaving with high-tech engineering to give delicate but durable physical forms to abstract, scientific data.

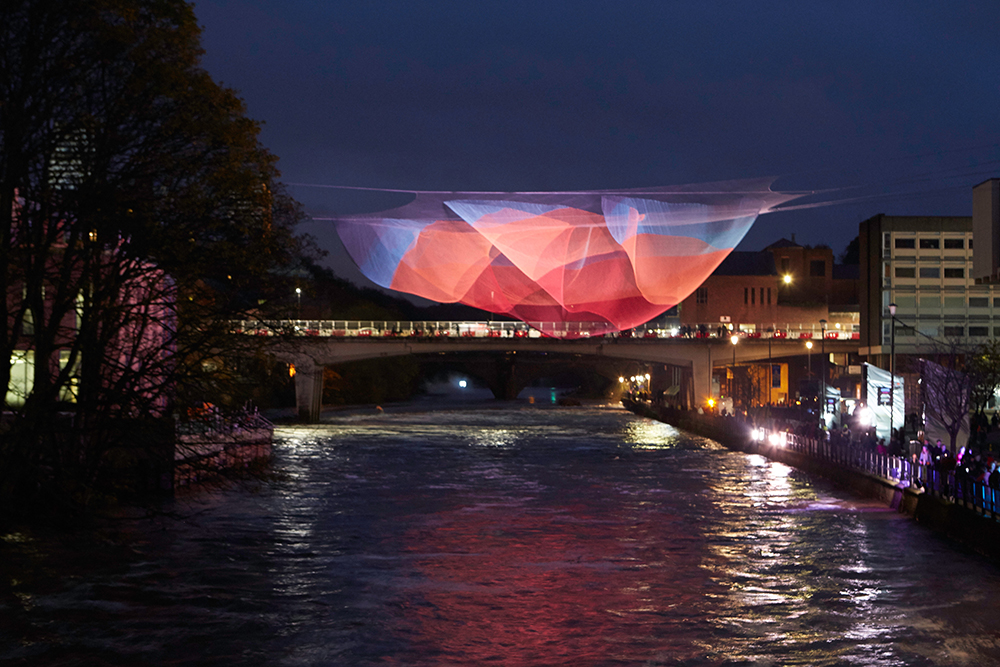

The catalyst for her sculpture, 1.26 was the tragic effect of the 2010 Chilean earthquake and tsunami, which caused vibrations so powerful that the earth’s rotation accelerated, shortening the length of the day by 1.26 micro-seconds. Using data from NASA which measured the height of the waves, Echelman and her team created a 3D image of this natural event. The resulting sculpture, which hovered like a hologram above the Wear, showed how interconnected our world is; “when one element moves, every other element is affected”. During Lumiere, visitors were able to interact with the sculpture digitally by manipulating the colour projected onto it using an app designed by Art AV (supported by Atom Bank). The idea of interacting with artworks through the small screens of our smartphones is one that might seem at odds with the collective joy of Lumiere and yet Echelman believes that digital advancements can, when used imaginatively, connect us to one-another: “It’s not the phone that distances us…We can use it in a way that brings us together in a real landscape in real time in a real conversation”. Through their phones, audience members could reshape their experience of the sculpture, reiterating the idea of cause and effect which inspired the work.

Although she’s been credited with changing public spaces worldwide, Echelman has never formally studied sculpture, engineering or architecture. She set out to become an artist on her own and sought every opportunity to learn ancient crafts, travelling to study Chinese calligraphy, brush painting in Hong Kong, lace making in Lithuania, Buddhist garden design in Japan, before eventually settling on painting. While working in a disused squash court as Harvard University’s artist in residence, she was awarded a Fulbright Senior Lectureship in 1997 and flew to India with the intention of exhibiting her paintings around the country.

She arrived ready to start work in Mahabalipuram, a fishing port in South India, but her painting supplies, which she had flown out a few weeks earlier, did not. With her tools lost in transit, Echelman looked to her surroundings for inspiration. She initially began working with local bronze casters, but soon found the material too heavy and unyielding. While taking a walk along the coast, she watched the local fishermen bundling their nets into mounds in the sand and although she had seen them working a hundred times before, this time their fishnets sparked an idea in her mind: “A new approach to sculpture… a way of creating voluminous shapes without the need for rigid, expensive materials”. She created her first aerial sculptures, the Bell Bottom series in collaboration with these fishermen by hoisting her netted sculptures up into the sky on poles. Following this first series, Echelman’s net sculptures began to balloon larger and larger. She strove to shift from “creating something you can look at to something you can get lost in”.

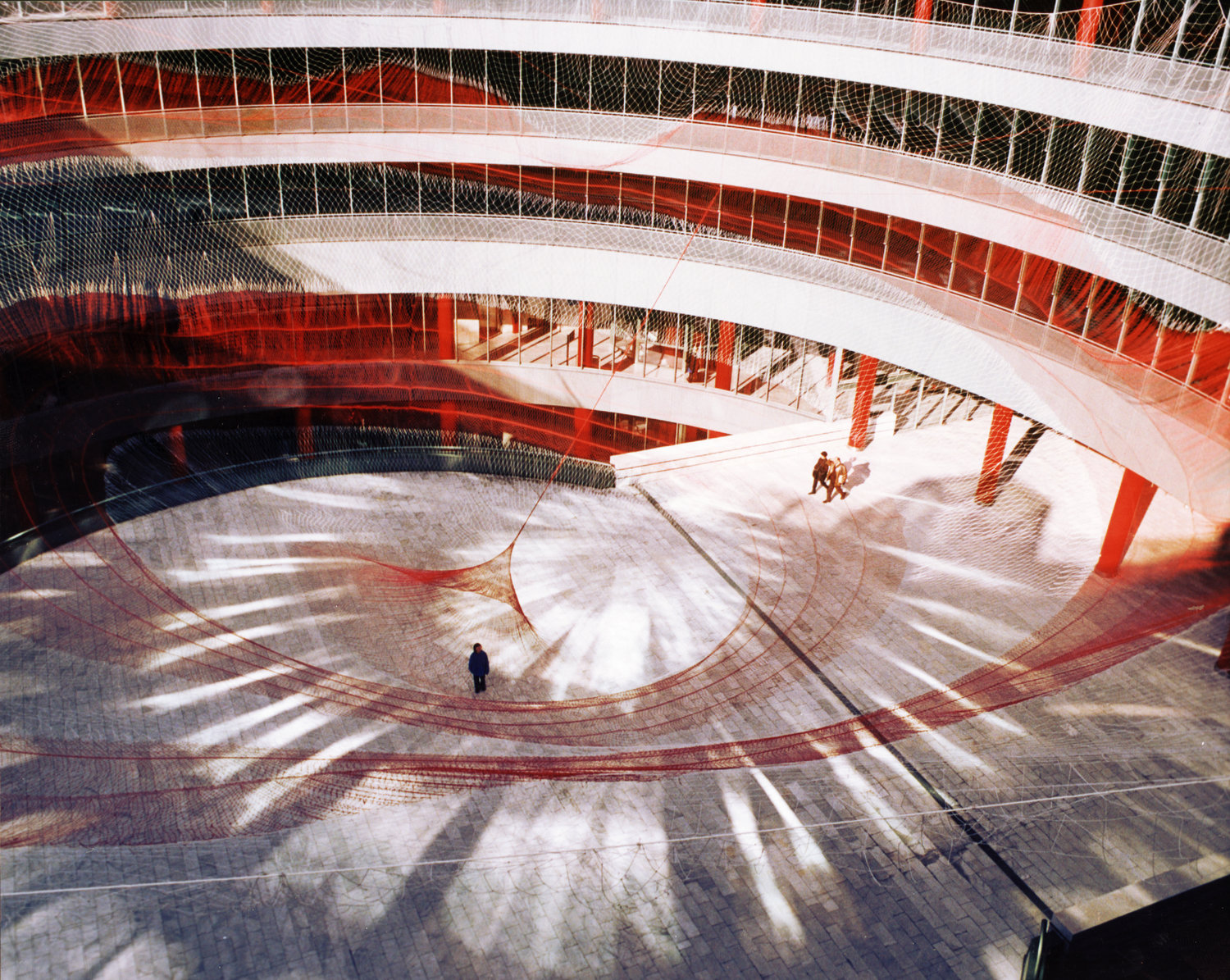

She later returned to India to work with the fishermen to create an enormous net made of a million and half hand tied knots for her Target Swooping series. These artwork were installed in public spaces across Europe and as a result, she was asked to create permanent artwork for a redevelopment in Porto, Portugal; a challenge which elevated her work to the next level. The project pushed her to find a new, fluid material to replace her hand tied net which would be strong enough to withstand UV rays, hurricane force winds, salt air and pollution. She began working with an aeronautical engineer to produce industrial strength crafted nets. Two years later, a 45,000 lb. steel ring holding 50,000 sq. ft of net was raised into the air to form She Changes, a permanent sanctuary of sculpture on Porto’s waterfront.

Echelman’s work continues to evolve. As the concepts behind her work become more intricate, so too have their physical structures, driving her to replace the metal armatures used in her older sculptures with a new soft fibre mesh. This high-tech material is fluid and light, but 15 times stronger than steel meaning that her more recent sculptures are so light that they can be tied mid-air to existing buildings, “literally becoming part of the fabric of the city”. Echelman’s sculptures in public spaces and above streets are designed to interact with people and instigate conversations in the context of our daily lives: “Why are we making art if it’s not about life?” she asks. In 2016, for Lumiere London, 1.8, a new voluminous net sculpture was suspended 180 ft. in the air between buildings above Oxford Circus. To install the structure, the surrounding roads were closed overnight while its four corners were winched up above the street and for the duration of Lumiere London the junction on Europe’s busiest shopping street was pedestrianised to allow people to stop and gaze upwards and notice the changing patterns of the wind. Since Lumiere, the sculpture has travelled to San Diego, Mexico City, Beijing and Xian, inspiring passers-by in each city to pause and slow down for moment next to people they don’t know and “share the rediscovery of wonder”.

Quotes are provided from the following articles:

Janet Echelman, 2011 TED Talk, ‘Taking imagination seriously’