Listen to this blog post:

Tony Heaton is an acclaimed British sculptor and disability rights activist who was appointed an OBE in 2013 for services to the arts and the Disability Arts Movement. He has been practising as an artist since 1972, and works in a variety of mediums including direct carving, assemblage and performance, often reflecting upon a disabling world and offering powerful critique of the barriers disabled people encounter.

Having exhibited nationally and internationally, Heaton creates work for both private commissions and in the public realm, with major commissions including Gold Lamé, the first sculpture on the Liverpool Plinth in 2018, and Monument to the Unintended Performer, installed on the BIG 4 outside Channel 4 TV Centre, in celebration of the 2012 London Paralympics.

Heaton speaks of his experience as both an artist and an activist as being blurred – one nourishing the other. Working throughout his career to promote social justice through a number of disability and diversity-related roles, he was previously Field Officer for RADAR (now Disability Rights UK), Development Officer for NACAB Citizens Advice, Director of Holton Lee and CEO of Shape Arts, which he has Chaired since 2017. He joined Artichoke’s Board of Trustees in 2022.

Today, we’re in conversation with Tony Heaton to discuss how his work as a disability rights activist informs his artistic practice, attempting to answer the age-old question: what came first, the idea or the visual aesthetic?

When somebody asks me that, I always start off with the fact that when I was a kid, I was happiest in Winter, at night, laid on the carpet in the living room with a pad of scrap paper and some pencils, and I just used to draw.

As I got older, I was out playing in the fields, fixing motorbikes, riding… I always fixed things, or took things apart, and I think that’s where the sculpture bit comes in. It’s that idea of construction and deconstruction, which was kind of always part of my life, and I get it from my dad, really, because he would always fix things.

I’ve kind of had a twin-tracked career. I always drew, always made sculptural things and in between I had my formal education. But I’ve always worked. When I left university, I was married and had a child, so I got a job in an organisation called RADAR. I was, what they called back in the day, a ‘Field Officer’ – I worked out in the Northwest of England developing disability rights. It was during that time that suddenly disabled people woke up to the fact that it wasn’t their impairments that were stopping them doing things, it was the way society was constructed. Hence the importance of the Social Model of Disability.

It’s interesting talking to people, isn’t it, like curators? A curator a while ago, he said, “Well, you alter things, don’t you? Really, that’s quite the nub of a lot of your practice, where you get something and then you alter it, either subtly or overtly, and you change it into something else.”

I made a sculpture called Gold Lamé, which was a three-wheeled invalid carriage that I was issued with when I had my spinal injury. I always say I transmuted from a biker into an invalid and I swapped a motorcycle for a wheelchair. My mode of transport became an invalid carriage. Invalid carriages were always blue and they marked you out as a cripple basically. You were kind of outed by the form of transport.

They took them off the road in the 1980s, but I thought, “you know what, wouldn’t it be great to find one”, and I bought this scrap invalid carriage, carted it back, did lots of work on it, and sprayed it gold. Everything was gold. It was a commission for DaDaFest for the ‘Art of the lived experiment’ And it was hung from the ceiling of the Bluecoat Gallery and I called it Gold Lamé.

I said, “Well, from lame to Lamé. From spazz blue, to gold.” So, it’s this idea of transmutation, of changing things.

I have this really early work, Great Britain from a Wheelchair, made out of bits of old wheelchairs mapping out Great Britain. [It made] a statement about what it was like to be a wheelchair user in Britain. Somebody said, “Yeah, because we’re all over, aren’t we?” And we are all over, wheelchair users, we’re everywhere!

It’s quite interesting actually, my first real political action was when my local art gallery, the Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library in Preston, closed to do some big-time refurbishment back in the 1980s.

I was really looking forward to the reopening. They had built a mezzanine floor with a staircase at either side and you walked around the gallery. I understood the logic, “We’ve got this massive room, and we can create another half of a room all the way around it.” But I went in when it opened and said, “Well, how am I going to get up there?”

They had received money from Harris Bequest, a solicitor who bequeathed a huge amount of money to Preston for the furtherance of art, and in his bequest it said “For the poor people of Preston.”

So, I got in contact with Preston Council and said, “Most of the poor people in Preston are disabled people – that’s statistically true – and you’ve just spent a vast amount of the Harris Bequest building an inaccessible aspect to your art gallery.” So, I wrote to Harris Bequest, and said, “You’ve given this money under false pretences.”

And they went, “Crikey, he’s got a point!”. They withdrew the grant and Preston Borough Council had to stump up all the money for it, following that they began to consult with us on access across the county.

Well, I always thought, I’m a working-class guy at art college, but need to make a living. I’m going to have to do graphic design, which I hated. I made a living as a graphic designer for a while, but I always wanted to make sculpture. I can’t paint – I don’t have any sense of colour; any sense of which colours go together. I still paint for my own pleasure, but I don’t think in terms of painting, I think in terms of sculpture. And I think more often in terms of carving.

They always say there’s two sorts of sculptors: there are the ones that stick things together and the ones that take things apart. And I’m by and large a take-things-apart merchant. So, you start off with a big lump of stone, and you hit it with a hammer and a chisel until you get a smaller lump of stone and hopefully something that you’re relatively happy with as an object.

I think your character is expressed in your work and I guess I’m a bit of a subversive joker. So, naturally that comes out in my work and not necessarily intentionally. It just kind of happens. I like to think the work is multi-layered, so that people can approach it from different points of view and still get something out of it.

I often use the example of A Bigger Ripple, which is the Artichoke-supported neon that I did for Lumiere Durham in 2021. It’s a neon in cruciform and it says Raspberry Ripple. Raspberry runs down and Ripple runs across. There’s two Ps in Ripple, and one P in Raspberry. When I was playing around with the idea, literally writing it, I was thinking “How could that look?” I like stuff like that, it was a kind of an intellectual puzzle, I suppose.

Hardly anybody ever notices that I’ve taken the P out of Raspberry, which is a silent P anyway. If I say, “Oh, what do you notice about this?”, they’ll say, “Oh, it’s sexy. It’s pink, it reminds me of that stuff you swirl on top of an ice cream.” They’ll never say, “There’s a P missing.” And that’s the deficit model around disability: people perceive disabled people to be somehow less.

Of course, ‘Raspberry Ripple’ is also rhyming slang for ‘cripple’. So, if you’re disabled, politically astute as a disabled person, you’ll get it straight away. You’ll go, “Raspberry Ripple – cripple.” It’s a crip joke. And you’ll laugh, because it’s an audacious crip joke. But it’s subversive, in the sense that most people won’t get that.

There’s another neon in my current exhibition altered, it’s called Tragic Brave, and again, it’s cruciform with the A. I exhibited at the Grundy Art Gallery in Blackpool last year and a young disabled woman said, “When I saw that, it smacked me between the eyes.” She had an invisible impairment and she said, “When I explain to people I’m a disabled person, they say two things to me: ‘Oh my God, that’s tragic’, or, ‘Oh, you are so brave, going through all that’. So as soon as I read those two words together, it was like, yep, that’s my story.”

Disability’s a very open and welcoming club. The older you get, the more likely you are to come and join us, and that’s a bit terrifying, if you’re not disabled, isn’t it?

Well, I guess I would go back to 1991, when I made Shaken Not Stirred, which is the pyramid of red charity collecting cans.

There was this awful thing on the telly every two years called the Telethon – a 24-hour begging fest for disabled people – and they said “Okay, we’re going to raise a few million quid.” I worked out that it was two quid for every disabled person, which was what a pint of lager cost. So, basically, they were buying a pint for every disabled person in Britain. The general public thinks, “Wow, millions? That’s fantastic.” But it’s the equivalent a pint of lager every two years! And the negative stereotypes that were portrayed were false and damaging and far outweighed the pint of lager that I was going to get as a disabled person.

Shaken Not Stirred was a performance piece. I threw this prosthetic leg with a Doc Martin boot into the pyramid at the press conference and it was this idea of the destroying the hierarchy of charities. Shaken Not Stirred is the idea that we shake a can, the people put a quid in it, but their conscience is not stirred.

So that activism still exists for me. I want to spread evangelical words, provoke conversations about the way that disabled people are treated and continue to be treated. It’s not changed. That’s the sad thing.

It’s sort of a bit of both. Sometimes, it will be something I’m thinking about and then I think, “Oh, yeah, I could express that sculpturally.”

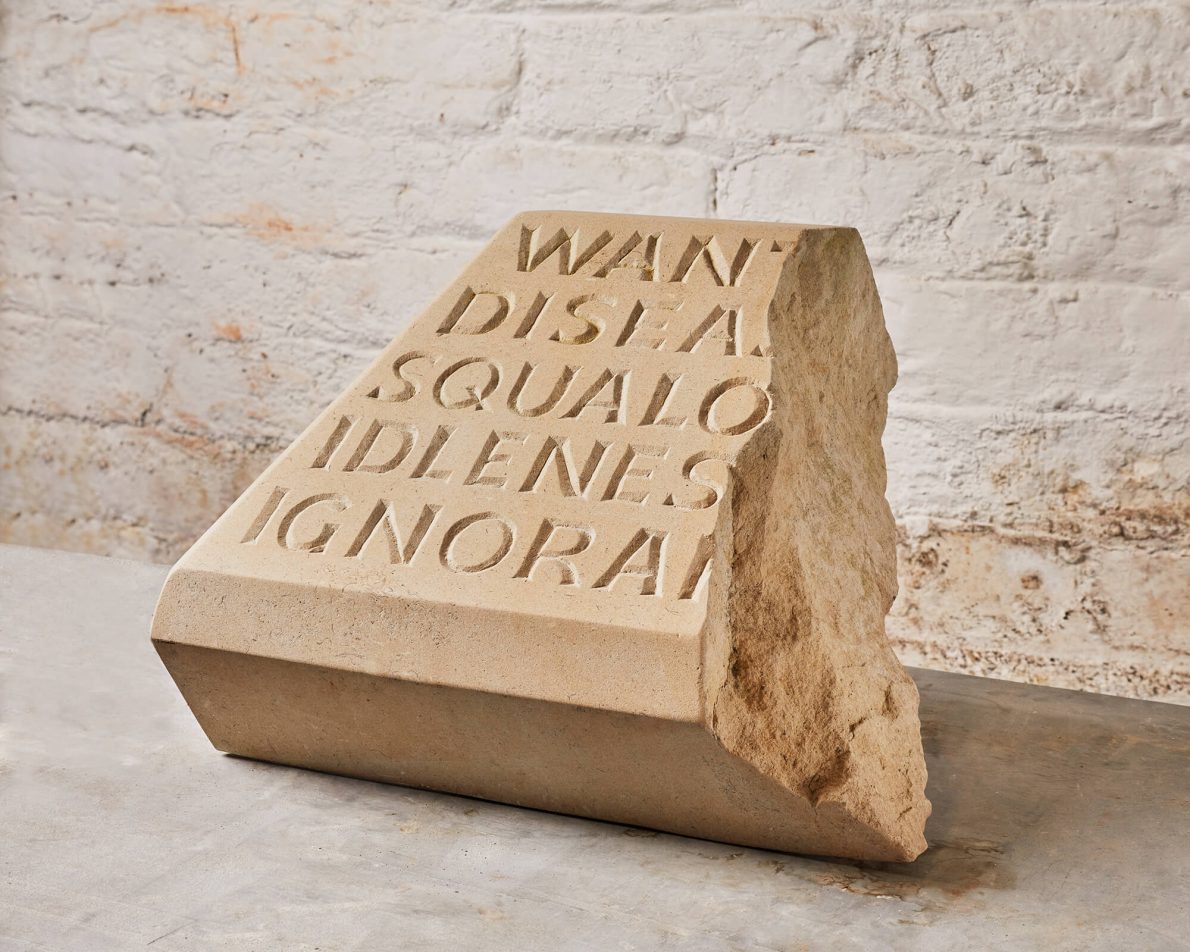

In 2017, on the 75th anniversary of the birth of the welfare state, I was in my studio carving away… I had this piece of stone from a stonemason, a ‘keystone’. It’s a really important support system for a stone arch, but it was broken. It had chunk broken off it.

The work is called Damaged. I like things that are damaged, or broken, or whatever. And I think, how can I keep that alive in some way?

I was listening to the radio and suddenly I looked at this keystone and I thought, Beveridge, the father of the welfare state said, “We need to get rid of five giants.” And they are poverty, want, disease, idleness, and something else that I’ve forgotten… He said, “When we’ve rid ourselves of that as a society, we will truly be a civilised society.” And I thought, bloody hell, those five things are still with us. We’ve got people sleeping on the streets. We’ve still got poverty, food banks… and I was looking at that keystone and I thought, you know what, I could carve those five words into that broken stone. You didn’t need the last two or three letters of each word, you’d guess it.

I wanted to cause confusion [around whether] “those words were carved into the stone, and then the stone was broken? Or was the stone already broken, turned upside down, and somebody’s carved the words into it?”

So, it often starts with an idea, and it can be completely random, but it might be about disability… It’s things that I think or feel strongly about, and then I think, “Okay, I’m going to hold onto that, and think about what it could be, in terms of a piece of sculpture”.

Well, there are a lot of practical things you can do, but it means being hardline as an organisation. It might be a bit radical, but there’s nothing stopping you doing it. It means not just going, “Oh, well we’ve always done it like that. And it will be quite difficult to move office to be more accessible.” It’s not really, is it? If the accountant said we can’t afford the rent anymore, you’d have to move.

Olafur Eliasson had a large exhibition at the Tate Modern a while back, and he had a piece of sculpture that you could walk through, but it had steps. I said “Well, just refuse to show that piece.” And they responded with “Oh, we can’t do that.” Yes, of course you can. Why can’t you? I said, “He’s got loads of work. You’ve got to say to him, ‘We need to ramp this.’ And if he refuses, then say, ‘Well, we don’t want the work, because we don’t want any of our audience to feel excluded.’”

Do you think he’s going to refuse to put his work in the Tate, or any other publicly-funded gallery because you’ve refused one of his pieces? I don’t think so for one minute. He’ll just go, ‘Okay, here’s another piece, and maybe I should modify that work.’

I think in the ’80s, when I was a young activist, people were willing to do that kind of stuff. Nobody wants to make decisions anymore. They all want to defer it to somebody else, or do nothing about it… I think there’s waves of apathy, that’s why we’re slowly falling apart as a nation. I don’t necessarily agree with what’s happening in Paris right now [regarding President Macron’s pension reform] but I kind of have a grudging respect for them, to say, “no, we need to say quite strongly that we are against this. And we can’t just let faceless men in suits make bad decisions that have huge impacts on us all.”

It’s about power and rank. People say, “Why did you take an OBE?”. They wouldn’t imagine that I would, but it opens doors that allow me to get in and try and affect change.

So, I can say, “We should be having more disabled people’s stories in museums and galleries. We should be employing more disabled people.” And then people in power listen and they might take notice and change happens. In a small way, it is about trying to force change and make people aware of things.

Being on the Board of Artichoke means that I can offer Disability Equality Training and hopefully you and your colleagues will think about things in a different way, which you are doing. And that’s great for me, because it means some people who have power and influence are going to make a difference, or collectively make a difference.

That started probably 30 years ago. I was living in Cumbria and making sculpture, and I was having a conversation with a poet and writer called Allan Sutherland, moaning about the fact that disabled artists’ works never appeared in galleries. He was saying, “As we die, our work will just disappear. We’ll just be this thing that popped up, and there was some work by disabled artists that were politically driven. And then we all died, and the works got chucked away, and that will be the end of it.”

I thought, Christ, that’s absolutely right. That’s what’s going to happen. And then I just happened to get this job, at Holton Lee, as director. I started to programme disabled artists in this space I developed and I’d say to the artists, “if you want it to continue, just leave me a piece of your work, and it can stay here on permanent show.”

So, I started an ad hoc collection of these works, and then I started to think, “Well, maybe at Holton Lee we can build the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive.” I had these three-day conferences, to say, “How do we go about doing this?”

I started it at Holton Lee, took it to Shape in London when I was recruited as CEO and it’s actually now at the New University Bucks in High Wycombe, which is a much safer place for an archive to be. It took quite a long time to make it happen, but I’m glad it’s happened. And I’m glad there’s a website and there’s ephemeral objects that have been collected, there’s books about Disability Arts in the University Library and we have a repository, with real works of art in it. So, if you make an appointment, you can go and see paintings and sculptures and real objects. And we can all die, knowing that the work’s collectively at least somewhere on a website, or in a collection, or whatever. And people can’t deny disability arts, because it exists. As well as putting the suffragettes, or gay rights, or whatever it is [in collections], curators can also include something around disability rights and the fight for anti-discrimination legislation for disabled people.

I’m in negotiations with the Yorkshire Sculpture Park to site Gold Lamé there, so, hopefully that will come off! For a sculptor, to have something at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, is kind of like the pinnacle of where it’s at.

Then, this time next year, there will be the first ever exhibition of work by disabled artists, DAM in Venice – the Disability Arts Movement in Venice. It’s a collection of work by disabled artists at the Biennale. I think I’ve got five works in it, including Gold Lamé. Again, that’s in negotiation. But I’m pretty certain it’s going to happen and it will be the first time that a collection of work by disabled artists has ever been exhibited there. They’re two things that are hopefully materialising in my world.

Tony Heaton: altered is on from 24 March – 25 June 2023 at the Attenborough Art Centre, Leicester.